News, events, articles

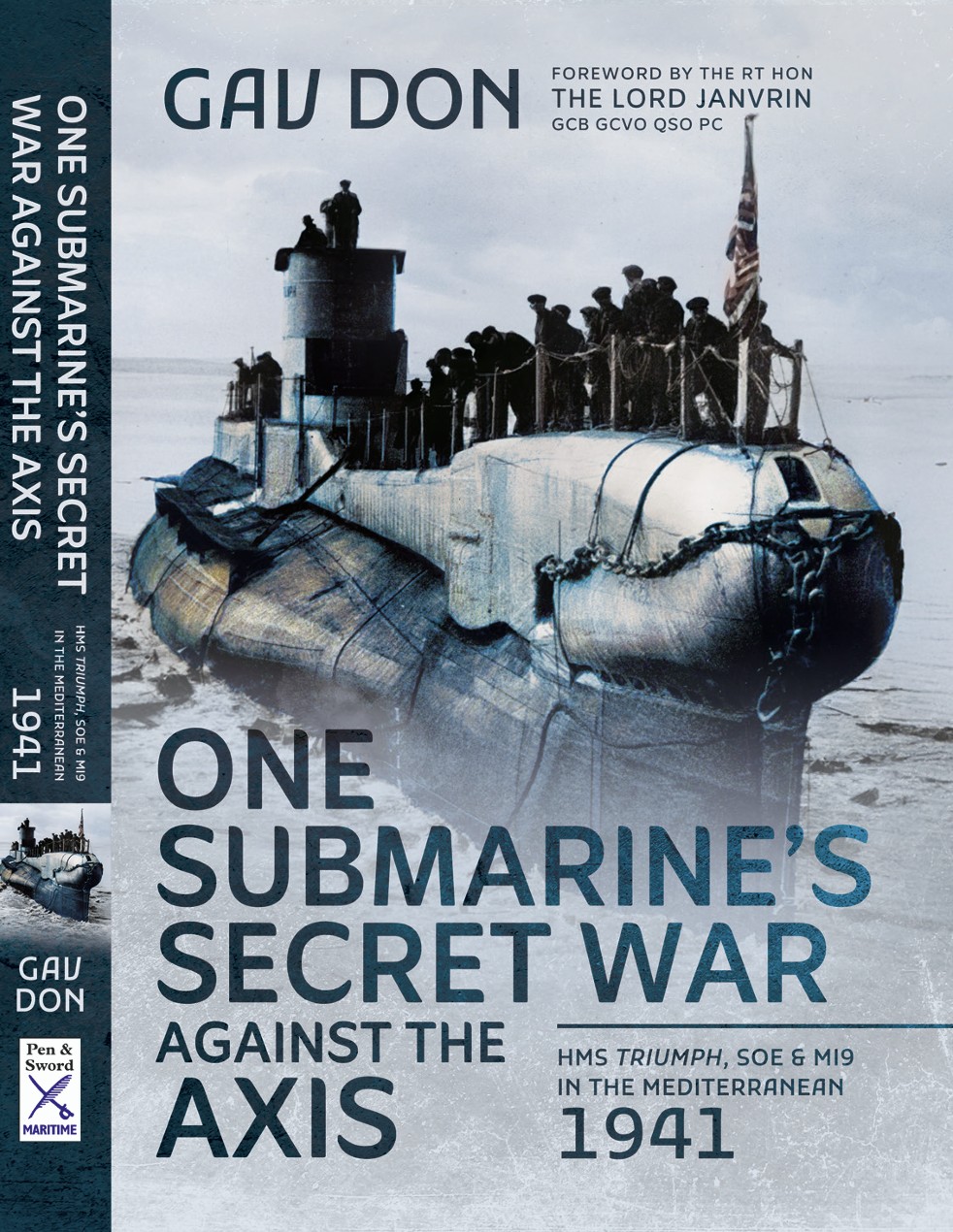

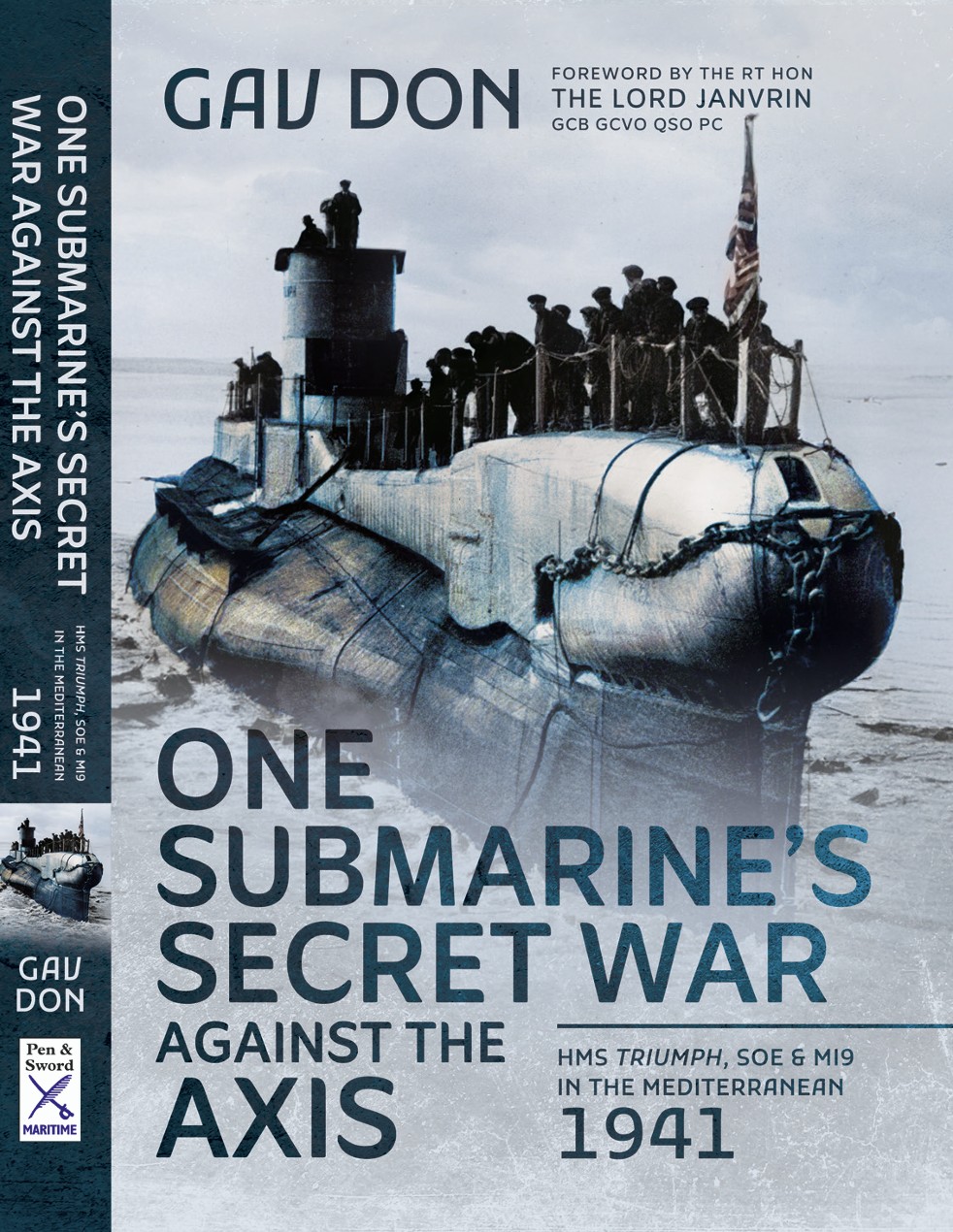

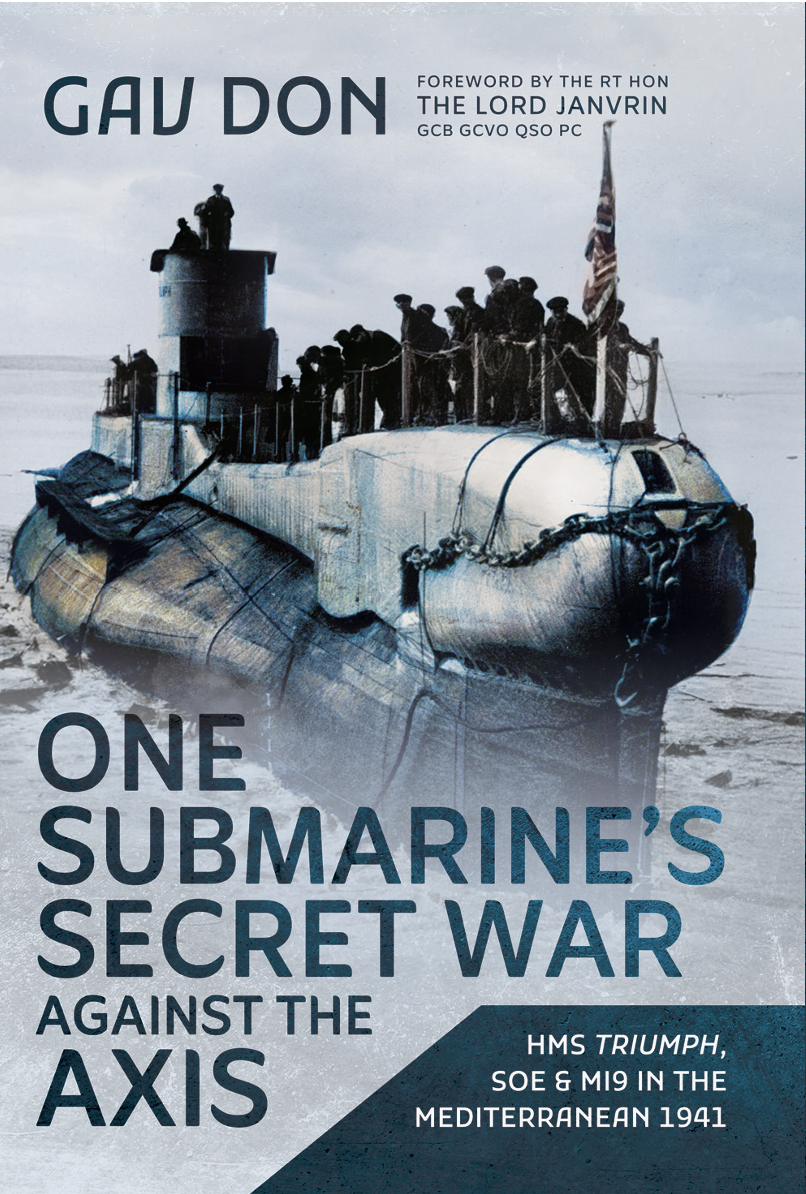

News, events, articlesThe book of the Triumph story is now available on Amazon. The book tells the story of the boat and her crew over the whole of 1941, and of how she became involved in the fall of Greece, the work of SOE, MI9 and escaping POWs afterwards. The book also follows the stories of three of her key agents, the New Zealander Jim Craig, John Atkinson of the RASC and the Greek smuggler and resistance member Harry Grammatikakis. We follow them into Greece, then into hiding in Athens, and finally into Triumph’s fated last patrol. The mystery of Triumph’s disappearance is answered.

Buy your copy on Amazon here

Rosie Corbin, daughter of Captain Richard Gatehouse RN, gave us a link to her father's oral memory held by the IWM, which can be heard here...www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011948

Gav presented the Triumph story to the current class of Phase 2 and 3 submariners at the RNSM School in Raleigh. Four copies of One Submarine will be presented as class prizes this year.

More photos of Raleigh can be found on the HMS Triumph Facebook page here www.facebook.com/profile.php

The book of the Triumph story - One Submarine's secret war against the Axis - is now out and in Amazon and all good bookshops.

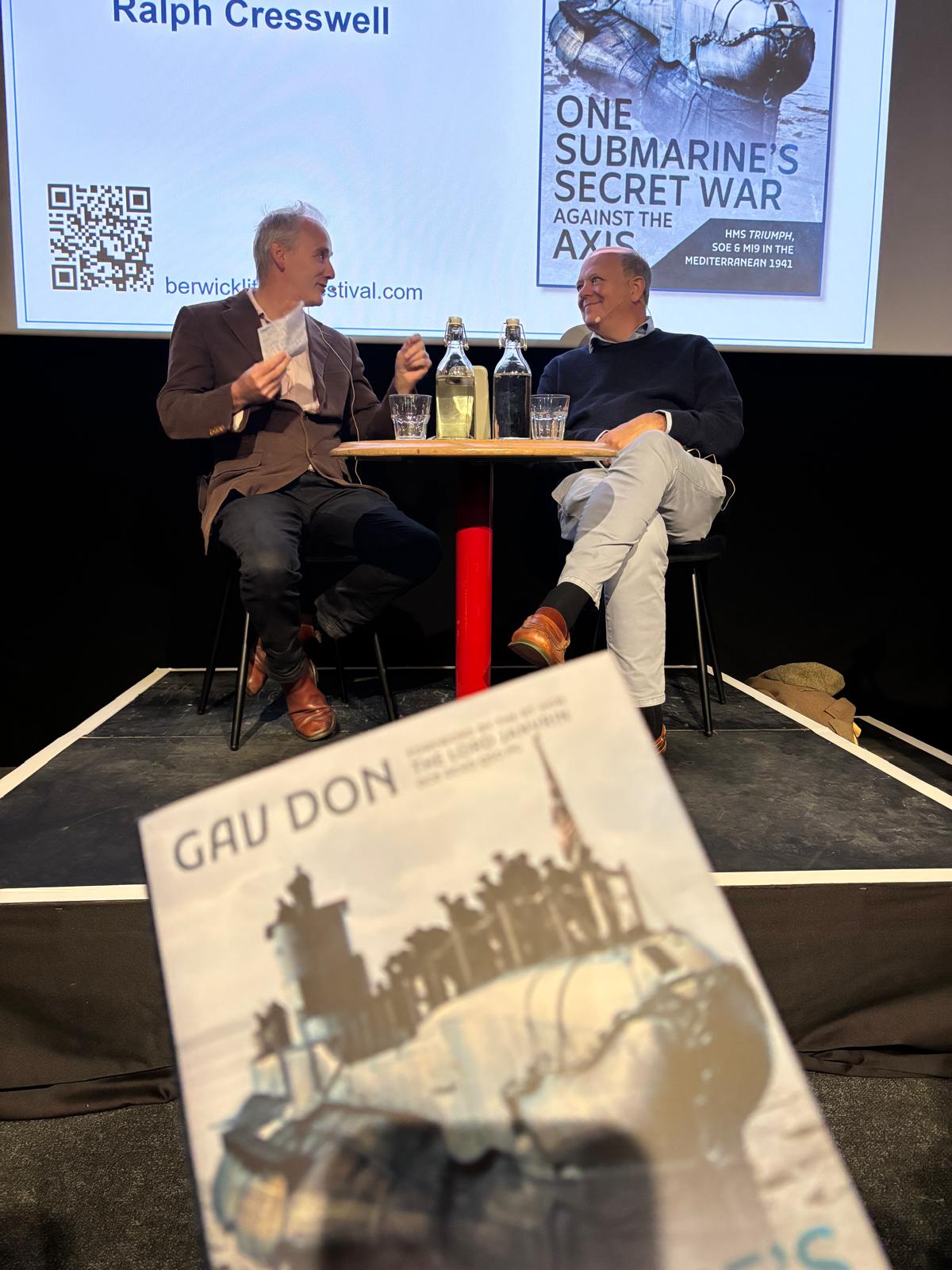

Gav was invited to present it at the Berwick Literary Festival on 13th October, where he was interviewed for an hour by Ralph Cresswell.

A video of the event can be found on the Triumph Facebook page at Submarine Triumph 1941, or on youtube here youtu.be/TKVFxvy0ZaM

This is the final version of the cover of the upcoming book about Triumph, 'One Submarine'. It is coming out in October, should be available to pre-order on Amazon soon.

Our dear friend and mentor Commander John McGregor OBE has sadly died...

John was my mentor, and it is largely thanks to him that the Triumph Families Association exists, since I simply copied much of what he had already done with the Neptune Association. John became a firm friend as well as a supporter, and the upcoming book One Submarine is dedicated to him.

John at our first reunion at Alrewas in 2017 and at a Neptune reunion at HMS Neptune at Faslane

Here is his obituary from the Naval Review:

It is with great sadness I advise the passing of Commander John McGregor OBE Royal Navy on August 12th 2025 at the age of 88.

After a varied naval career, which included high pressure jobs in nuclear submarines, John McGregor was appointed as Engineer Commander of HMS Fearless in March 1982. At the time he may have thought that this would be a comparatively relaxing job, but all that changed when Fearless sailed with the Task Force for the Falklands War.

He served under an outstanding Captain, in Jeremy Larken DSO, who allowed him to use his initiative in all sorts of ways. On the passage south, Fearless stopped at Ascension Island for three weeks and John visited every naval and merchant ship arriving there as the amphibious forces gathered for the future invasion. He was co-opted as staff engineer officer to Commodore Michael Clapp, the Commodore Amphibious Warfare. Virtually every merchant ship needed engineering help, having been assembled at breakneck speed before sailing. He had a large engineering staff of about 150, all happy to be involved, and Fearless became a fleet support ship.

Fearless sailed from Ascension Island on 8 May and entered San Carlos Water at 0230 on 21 May 1982. By mid-day 2,500 troops (mainly Paratroopers and Royal Marines) had landed by landing craft and helicopters from Fearless, Intrepid, Canberra and other ships. Later that day, and for the following week, they were attacked by Argentine Mirages and Skyhawks flying very low and fast – [too low to get their bomb delay fuses sorted]. After the landings, John’s team continued in their engineering support role of fighting fires (Plymouth, Sir Galahad, Sir Tristram), and repairing ships hit by bombs which did not explode and helping to remove the bombs. John was awarded the OBE for his leadership in removing unexploded bombs from Sir Lancelot and Sir Galahad. Regarding the unexploded bomb on Sir Lancelot, it was discovered that the fuse had unwound its full eleven turns and so it could have exploded at any moment only prevented because the spindle had been bent when the bomb had bounced around as it slowed down.

Peter John McGregor (always known as John) was born in Midhurst, Sussex on 1 June 1937 to Paymaster Commander John Harvey McGregor (known as Jack) and Audrey Pamela Brooke (known as Pam). Jack’s own father, Robert McGregor, was a Civil Servant in the Admiralty, who received an OBE himself. Pam’s father, Wynyard Brooke, was an architect who worked for 40 years in Shanghai and was ultimately interned there during the Second World War. Jack and Pam met in Shanghai where Jack was serving in the Royal Navy.

Jack and Pam lived in Surrey in their early married years but when they found themselves under the flight path during the Battle of Britain, they decided in October 1940 to move down to Devon. Jack drove down in his Austin Seven with John (aged 3) which left John with his only clear memory of his father. (Pam came down by train with younger brother, Richard, who was born in 1939.) Jack was posted to HMS Neptune, a cruiser, in 1941, and she sailed from Chatham in May on what proved to be her final voyage. The Neptune sank on 19 December 1941 when she entered an uncharted minefield in the Mediterranean off Tripoli, and all members of the crew except one lost their lives. From that time John’s life was inextricably bound up with the Neptune tragedy, and a major part of his later life was concerned with trying to unlock the mysteries surrounding the sinking and eventually finding the wreck.

John was educated at the New Beacon School, Sevenoaks, Kent, and then at Christ’s Hospital, Horsham, Sussex from the age of 12. He did well there, but at the age of 16 he followed his destiny by passing the exam to enter the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth as a naval Cadet. After the requisite two years, there followed a three-month spell in HMS Triumph, an aircraft carrier, during which they visited Leningrad (now St Petersburg).

After another year at Dartmouth as a Midshipman, he was posted to HMS Bulwark (another aircraft carrier) as a Sub-Lieutenant for a year which took him to the Far East and elsewhere. Then from September 1958 he spent three years at the Royal Naval Engineering College, Manadon, Plymouth. There he achieved the engineering qualification as a Member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers. John was always active in the sporting field and at Manadon he was Captain of Cricket, [performing as a batsman and a leg-break bowler]. He was also an athlete (representing the Navy in long and triple jumping) and he enjoyed rugby, hockey, squash, golf, sailing and skiing over the years.

His next appointment, by then a Lieutenant, was to HMS Belfast, a second world war cruiser known to many as she is now moored near Tower Bridge in the Thames. In Belfast he again visited the Far East.

His career then took a different turn in 1962 when he entered the Submarine Service. It started with a Submarine course at HMS Dolphin, Portsmouth. He then served in HMS Truncheon for two years and HMS Olympus for one year, based in Scotland and Portsmouth.

Then in 1966 he went on a Nuclear Reactor course at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, which was followed by nuclear training at Dounreay in Scotland. After being promoted to Lieutenant Commander in 1967 he was appointed to HMS Dreadnought, based at Rosyth and Faslane. The following year he was appointed to HMS Revenge, which was firstly based at Birkenhead and then at Faslane.

The final nuclear submarine in which John served was HMS Repulse, to which he was appointed in 1970, being based in Faslane and Rosyth. He enjoyed his time as Senior Engineer Officer of HMS Repulse where he spent 3 ½ years, which included three Polaris patrols and firing a missile down the range at Cape Canaveral. The refit in Rosyth Dockyard, including refuelling the nuclear reactor, took just 13 months which remains the fastest ever completed in a Dockyard. The engineering department worked in shifts day and night for the whole refit, which was crucial in driving the refit through to completion.

His three years in Chatham Dockyard from 1973 as Chairman of the Reactor Test Group taught him a lot about industrial relations, and he was instrumental in driving through the last six months of HMS Churchill’s refit, keeping her completion date on time. During this time he was promoted to Commander. He then spent a year on an advanced nuclear course at Greenwich gaining a Master’s degree. Then followed his most enjoyable time in submarine support jobs, with two years from 1977 as Base Engineer Submarines in charge of about 100 engineering and electrical staff, supporting all submarines coming in for maintenance and repair at Devonport.

His next posting was as Submarine Flotilla Engineer Officer on Flag Officer Submarine staff at Northwood for two years. Following that he was on courses in the Portsmouth area prior to joining HMS Fearless in March 1982, where his experiences have been described above. After his time in Fearless he spent two years as Naval Assistant to the Port Admiral Devonport, followed by an Intelligence Course and a special study in London.

Then in June 1986 he became on Intelligence Officer on the staff of the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) based in Norfolk, Virginia. It is the world’s largest naval station with many miles of waterways. John and his family enjoyed their time there and took the opportunity to enjoy water skiing. On returning to the UK in 1989 John was on the Naval Recruiting staff in London until retiring from the Navy in April 1991.

One occupation in retirement was the acquisition of a 40-foot yacht called Sea Biscuit in 1997. This was acquired together with a fellow retired Commander, Rob Walker, and John’s brother, Richard. Sailing trips were originally around the Solent but soon extended to the Scilly Isles and then to various parts of Brittany and Normandy. The Scottish islands were also visited, sometimes returning via Ireland, and one year there was trip to the Baltic. John carried out most of the maintenance from Sea Biscuit’s mooring in Chatham. The boat was kept for about 20 years.

John’s primary occupation during retirement was as Chairman of the Neptune Association, which was founded in 2002 to commemorate the loss of HMS Neptune and her fellow ship, HMS Kandahar, and to try and unlock the secrets relating to the disaster from which 763 men from Neptune had lost their lives, with just one survivor. The one survivor was Able Seaman Norman Walton. Richard had found a newspaper article about Norman in the Simonstown Naval Museum in South Africa, and from this John had established contact with him. Norman Walton attended the first meeting of the Neptune Association and recounted how he had endured five days on an open raft in the middle of December, seeing all his shipmates dying off one by one until he was picked up by an Italian ship. After Norman had died, the Association organised a memorial visit to Malta and Libya of which the highlight was a trip on a dredger out to the site off Tripoli where it was believed the ship had gone down. Norman Walton’s daughter scattered his ashes there. There was dramatic news in 2016 when the wreck of HMS Neptune was located by a Royal Navy survey ship, nearly 75 years after she had sunk. She was in almost exactly the place that John had predicted, and sonar images showed a clear correlation between the wreck and earlier photographs of HMS Neptune. John and other members of the Neptune Association were responsible for the creation of a pyramid memorial at the National Arboretum at Alrewas in Staffordshire which records the names of the 836 men who died in the two ships, Neptune and Kandahar. These events, and many other discoveries along the way, would broadly bring closure to the major catastrophe that had been a part of John’s memories for nearly all his life. He published his book recounting his research entitled “The Tragic Loss of HMS Neptune” in August 2025.

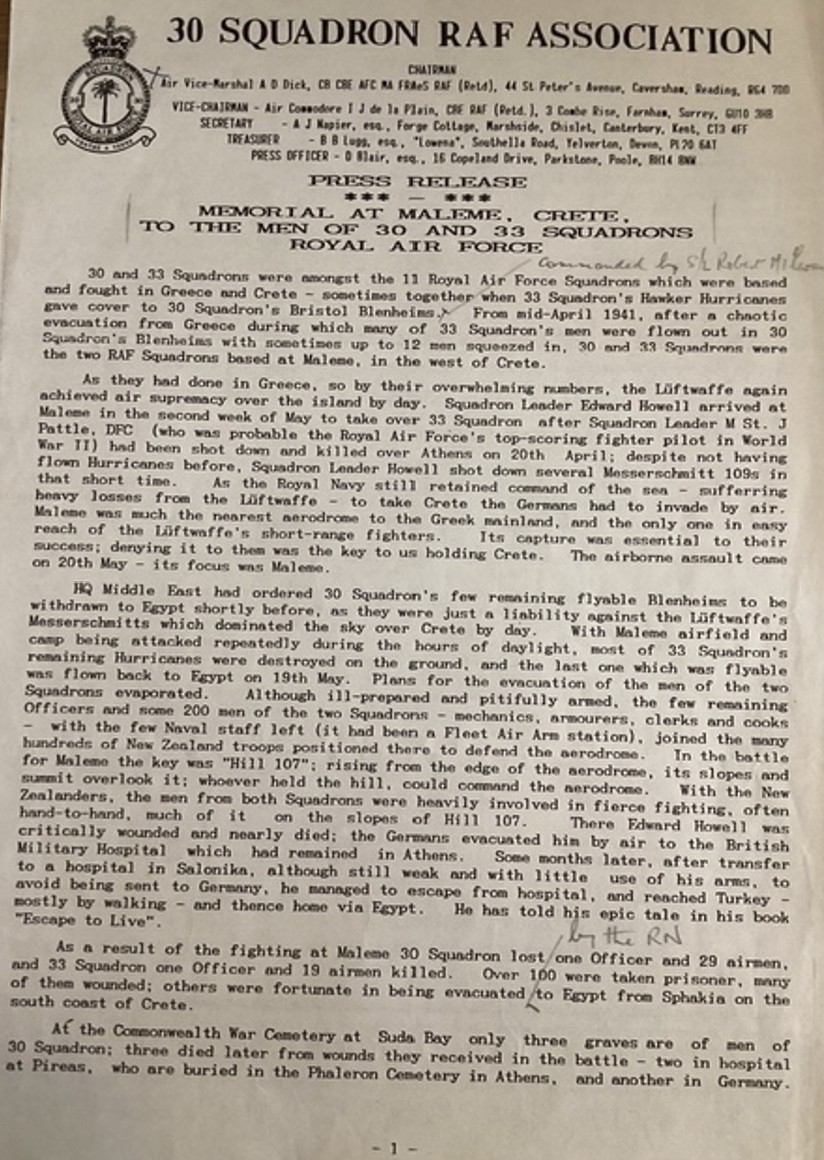

Flt Lieutenant Henry Daston RAF

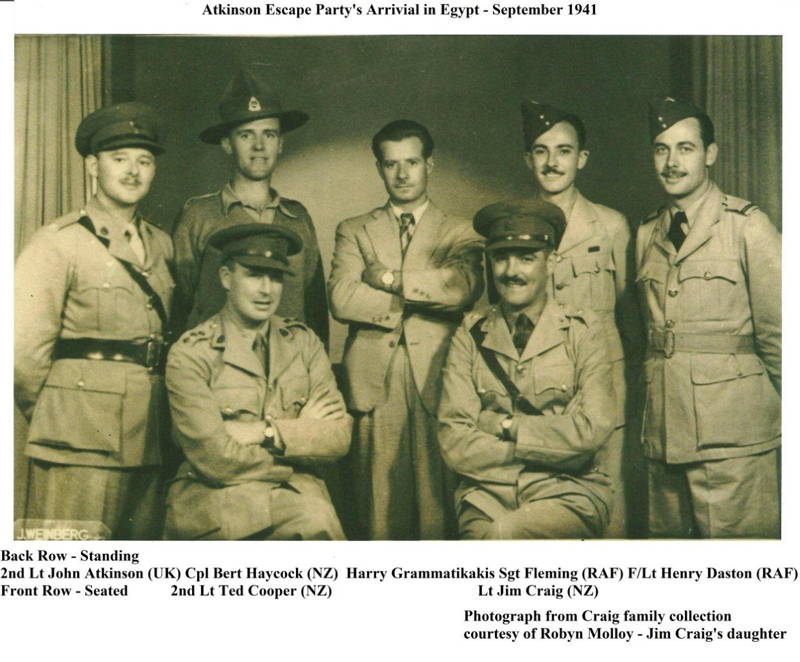

Henry Daston enters the Triumph story because he was in the Grammatikakis escape party with Atkinson and Craig, which arrived in Alexandria in October 1941. In the group photograph taken by Tony Simonds after that trip he is the man on our extreme right. Henry could speak fluent greek and turkish (and some Russian), learned during his childhood in Istanbul. It was Henry who helped the escape party pass through two German checkpoints by simulatiing a family row in the escape car with Miss Bourbouras in fluent and rapid Greek.

Henry entered Greece as the Intelligence Officer of 30 Squadron, a squadron of Blenheim's sent to Greece in November 1940 to help Greece fight off the Italian invasion. The survivors of that fight were withdrawn to Crete, where the last three aircraft left flying were withdrawn after the German invasion.

Henry, as ground crew, was left in Crete at Maleme Airfield, where he was when the German paratroop invasion began. He and his fellow RAF ground crew were referred to in the battalion history of 22 Battalion whcih can be found online, since Jim Craig's platoon was just a hundred or so metres from Henry and his men at the western edge of the airfield.

Henry's part in the battle for Maleme was also mentioned in the 1941 book Wings Over Olympus. 30 Squadron has a memorial at Maleme...

Henry was wounded at Maleme, and was therefore flown out of Crete to Athens very soon after being captured. Held at Kokkinia, he quickly escaped into Athens.

Hiding in In Athens Henry stayed with a family of two brothers and their mother, Andreas and Elias...

After his escape Henry was appointed to help train Greek volunteers in Egypt. After the war he appears to have joined one or other of the UK's intelligence services, probably GCHQ, where he worked until he reitred.

Henry Daston's daughter Cynthia and her husband Philip Sowden

Song of the Dolphins - a poem by submariner Bob Nicol...

Note - the Royal Navy's nuclear deterrent submarines - the Bombers - are currently serving 200-210 day patrols underwater. Originally designed to carry out continuous 60-day patrols, the submarine service's crews must now live with no communications home, no daylight, no fresh air, no weekends, no days off, no runs to the pub or movies, and no leave, for well over six months at a time.

Beneath the waves, where shadows dwell, The submariners set their course

With dolphins proud, their stories tell, Of silent depths and unseen force.

They embark on journeys, long and deep, A six-month voyage beneath the sea

In metal hulls, they vigil keep, Guardians of our liberty.

They set sail on a six-month trip, Submerged, unknown, their path concealed

A vital task, a secret grip, In service to the homeland's shield.

No daylight guides their steady march, In the abyss, they navigate

Their only stars, the sonar arch, In darkest depths, they contemplate.

No medals gleam upon their chest, At remembrance, they stand tall

With dolphins bright, their pride expressed, No need for accolades to call.

We guess their tales, in Russian seas, Shadowing subs, a silent game

In hidden depths, where dangers freeze, Their courage shines, without acclaim.

With every dive, their hearts hold fast, In narrow quarters, friendships bloom

In silent runs, their shadows cast, Across the ocean’s silent gloom.

Do these brave men seek glory's crown? No, for in their hearts they find

In dolphins' shine, their pride is bound, A symbol of their fearless mind.

They surface not for praise or fame, But for the duty they uphold

In their resolve, we find no shame, A legacy of stories bold.

Through waves they move, unseen, unsung, In service silent, deep and grand

Their song is of the deep well sprung, Their stories told by unseen hand.

So here’s to those who serve below, In submarines, with hearts of steel

In silent depths, where few can go, Their valor and their strength reveal.

July 2025

The noted New Zealand historian Paul London and his wife Julia visited Scotland while on a world cruise. Gav Don met Paul and Julia in Greenock and hosted them for the day, driving up to Inveraray Castle for a visit and lunch. Paul has spent many years researching NZ escapers and agenfs in Greece and Italy in 1941 and afterwards, and has indeed met most of them. These individuals, Jim Craig, John Redpath, Henry Daston, Francis Jones and others, are the men who will feature in the upcoming book on HMS Triumph's war in the Mediterranean "ONE SUBMARINE", which will be published in October by Pen and Sword.

We spent the day avidly comparing notes and sources, and talking about perhaps collaborating on a new book focusing on escapers and secret agents in Greece.

This is the upcoming book...

July 2025

On Friday July 18th the Subflot held a parade, Divisions, to celebrate the retirement of the seventh T-class submarine HMS Triumph earlier in the year. The parade celebrated all seven boats. The ship's company of HMS Triumph, aided by some comrades from other boats, paraded the White Ensign on the parade ground of HMS Drake, in Plymouth. 75 men took part in the Divisions, with a Colour Party for the White Ensign and a Guard. A band from HMS Drake provided the music.

Speeched were made by the Captain of the Submarine Training School, Captain Bushell, and by Lord Hamilton, who as Archie Hamilton was Minister of State for Defence when Triumph was launched, and whose wife Lady Hamilton acted as her sponsor.

The Triumph Association was represented by Gav Don, who took these snapshot videos of the occasion.

The band warming up...youtu.be/5l2q1kFI_Fk

Marching on the Colour...youtu.be/Mpu9alo2mOQ

The Colour Party and Guard are inspected by Captain Bushell...youtu.be/iMjJ_RxNbuk

Part of Captain Bushell's speech...youtu.be/jSJxVeSg26c

Part of Lord Hamilton's speech...youtu.be/vwyJtCty_fo

Captain Bushells' closing remarks...youtu.be/L7AGjgMC-g0

The Colour is marched off...youtu.be/jdwTKLJJ6aw

June 2024

On Sunday 2nd June 2024 42 members of the Triumph Family sailed out to the site of her wreck 15kms southwest of Cape Sounio in the Aegean.

Watch a documentary of the commemoration day on youtube here

Once we arrived on site we held a service of commemoration, led by Gav Don. During the service we laid 64 laurel wreaths (Triumph's crest is a circlet of laurel), one for each man in the boat. Each wreath was labelled with the man's name, and carried a family dedication selected by his relatives.

After the wreath-lay we were silent for one minute, then heard the last post, followed by three cheers for the ship's company of Triumph.

The group also visited the grave of Lieutenant John Atkinson MC*, who was shot at the Kaisairiani Shooting Ground in Athens by a squad of Germans in February 1943. Atkinson was the last man to see Triumph alive, when he was landed from her on the night of 31st December 1941.

We have received a generous donation from Angela Pugh, for which many thanks.

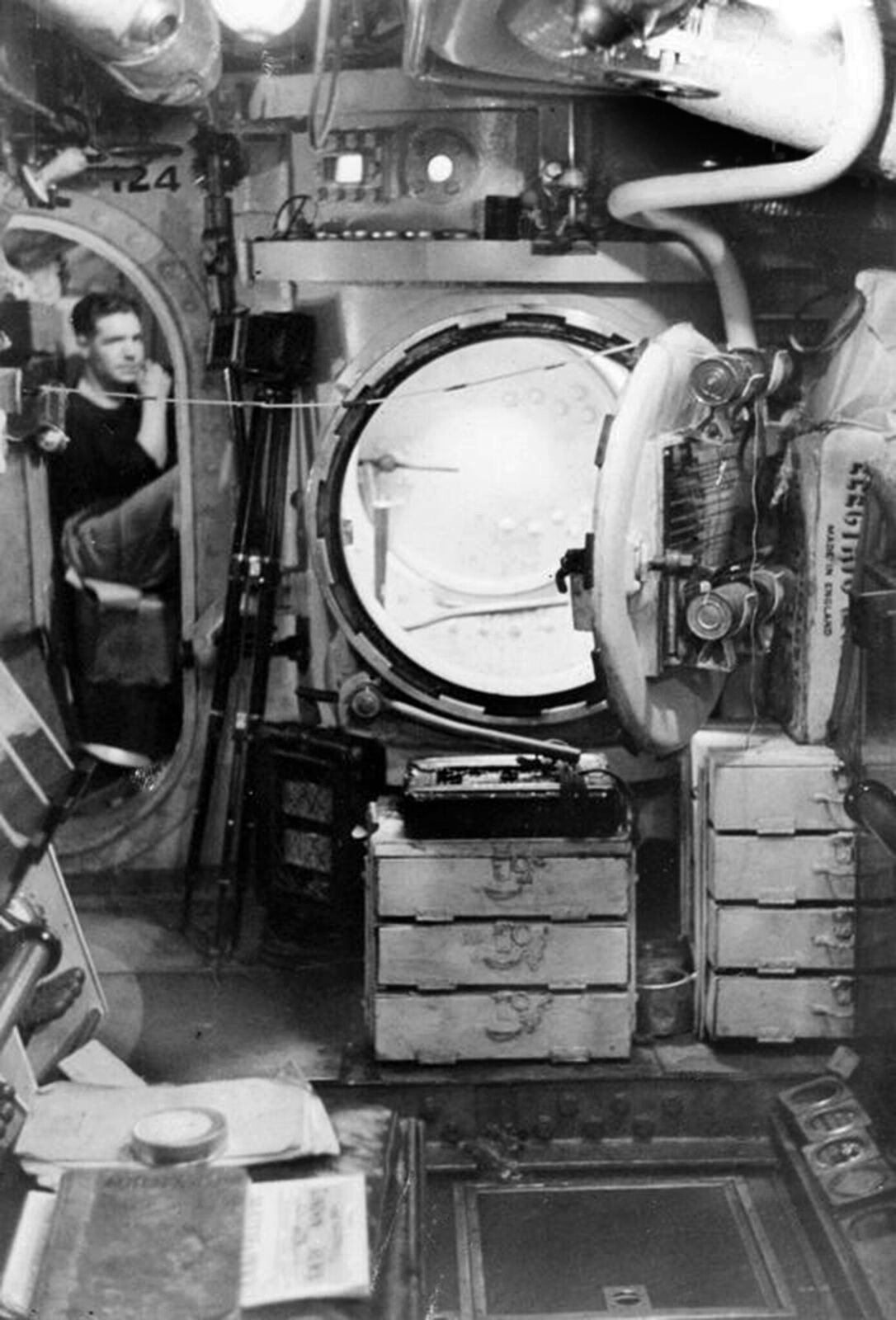

A marvellous collection of photographs of the interior of a T-boat has come to light in the Imperial War Museum collection. These were taken by the film crew who made Close Quarters, a 1942 drama about a typical T-boat patrol off Norway. The movie is a gem - all parts were played by servicemen, and it shows what a patrol was actually like. The photos were taken so that the set-builders could build an interior in the studio. The actual boat in the photos is Tribune.

All of these photographs are courtesy of the IWM, and we are also indebted to Andrew Jeffrey, of Dundee, who brought them to my notice.

We are gradually going to put all of these up, but for now here are a few...

This is the 1st Lt at Tribune's search periscope. Behind him is the blowing panel, which controlled the valves to allow air and water into the ballast tanks for diving and surfacing

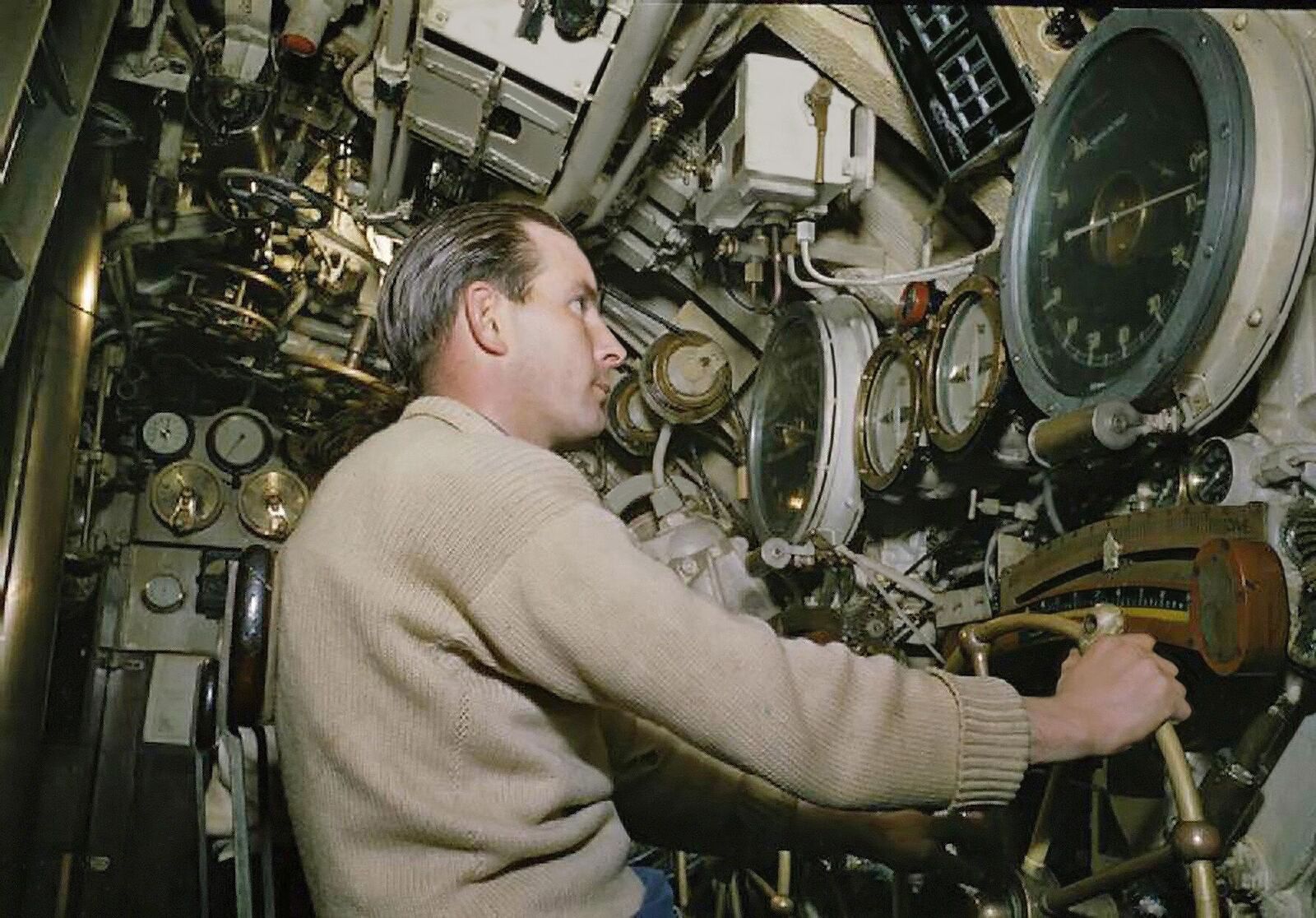

The boat's angle in the water was controlled by two men working the fore and after planes - small wings at each end of the boat. This is the foreplanesman. The large wheel adjusts the angle of the planes (using hydraulic "telemotors"). The big dial is the depth guage for shallow water, marked in single feet. At periscope depth the planesmen had to keep the boat absolutely level only a few feet from the surface to keep the periscope above the water but not visible. The brown guage below the depth guage is the clinometer, which shows the angle of the boat (like a spirit level). If the planesman lost control of depth the bubble in the clinometer would dive to one or other end of its glass tube - the origin of the phrase "losing the bubble" for being out of control.

T's had five messes, the wardroom, the Artificers' mess, the Petty Officers' mess, the Stokers' mess and the Junior Rates mess. Each was little more than a partitioned-off seating and sleeping area, but for boats of the time this was comfort indeed. This is probably the Junior Rates' mess. Tables are slung from the deckhead, and above the men to our right we can see bunks folded up against the pressure hull. Mugs hang on hooks on the bulkhead (doubtless named). Tribune was alongside the depot ship when these photos were taken so the men are comparatively clean and tidy, though wearing working dress.

Men relaxing in their mess after a meal. The boat is alongside the depot ship, hence newspapers and fresh bread. This is probably a staged photograph as when alongside Triumph's crew ate in the depot ship mess.

A group plays cards in their mess (we cant tell which one). Smoking is, of course, commonplace!

Another photo of a mess, probably the JRs again. There is a heater on the bulkhead - very welcome in the Arctic but not so much in the Mediterranean.

This is probably the Artificers' mess. The Tiffs were highly trained technical senior rates, each deep specialists in their fields. Tiffs could make or fix pretty much anything, given the raw materials and tools. Joel Blamey's book "A submariner's Story" describes the life of a tiff in boats, and is a wonderful read.

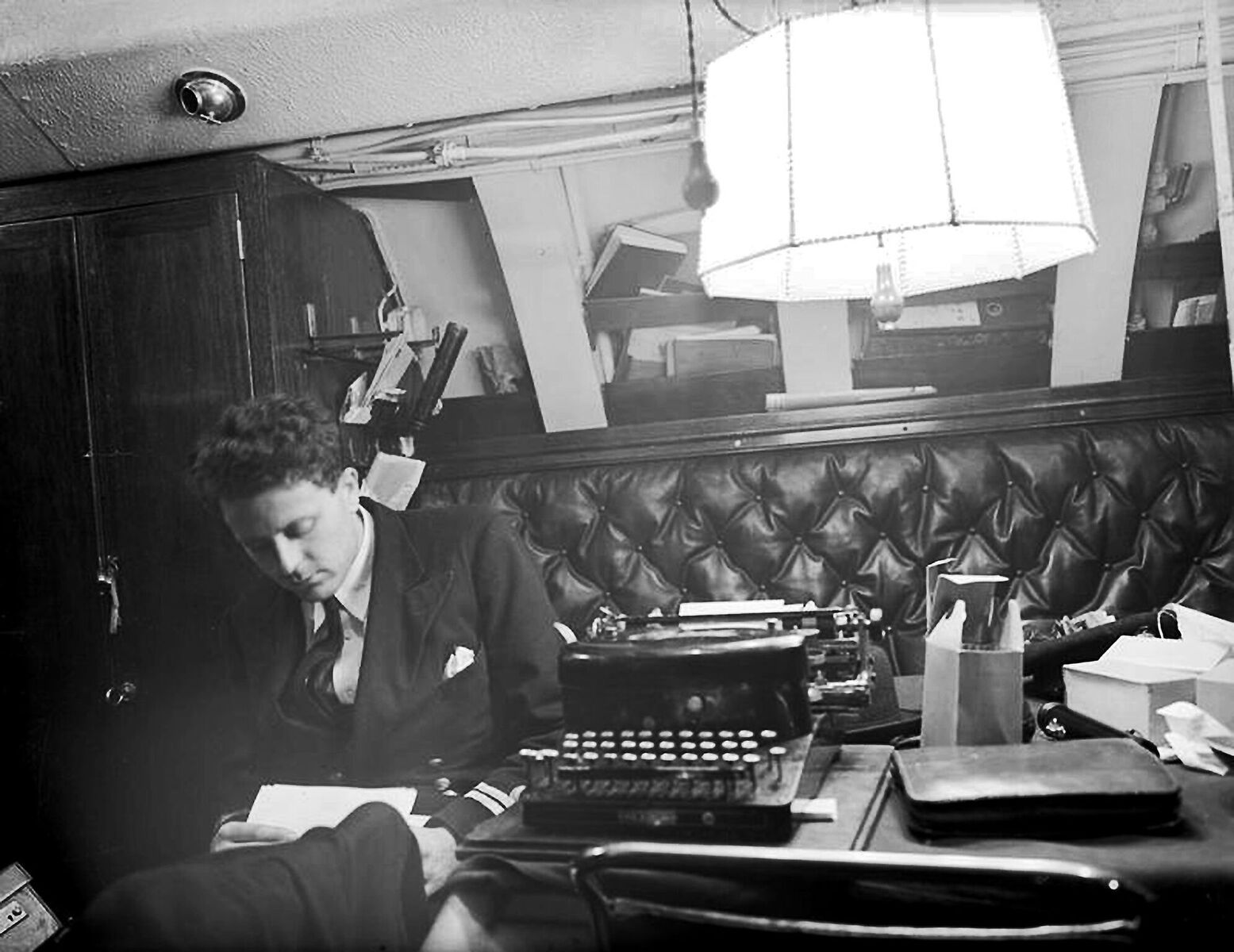

The Captain and officers messed in the Wardroom. The wardroom also served as the boat's office while at sea, hence the typewriter. Even at war, the admin of reports, returns, crew promotions and reports, and a multitude of other things had to be dealt with. The racks behind the 1st Lt's head are crammed with files and reference books.

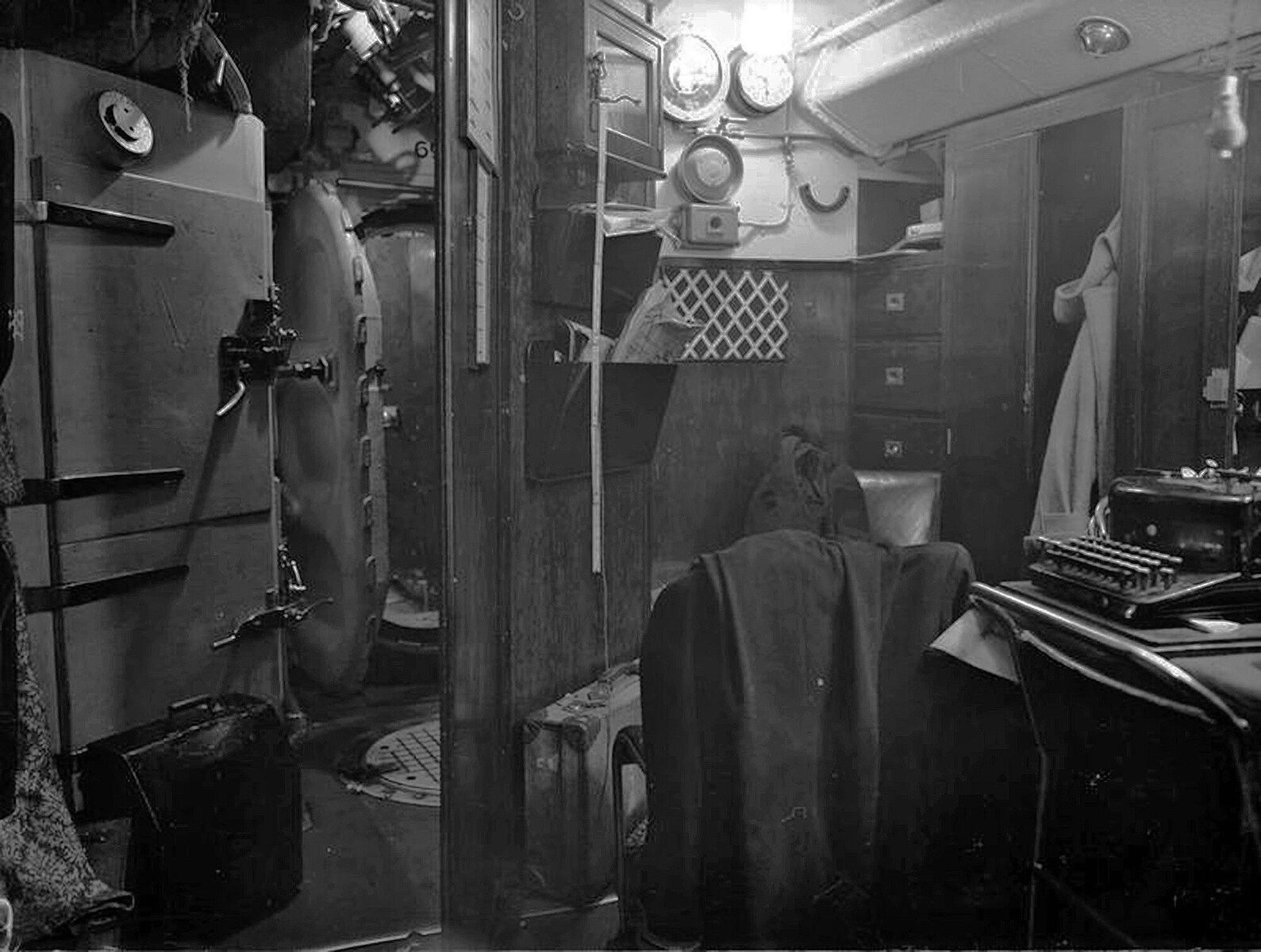

This is the wardroom, looking aft. The door is always open. A depth guage sits on the bulkhead to allow the captain to check the boat's depth even when relaxing. A foul-weather bridge coat hangs in the locker. Through the door we can see two large freezers for food storage, and in front of them is the wooden case for the typewriter. Behind the fridges is a watertight door leading aft to the control room.

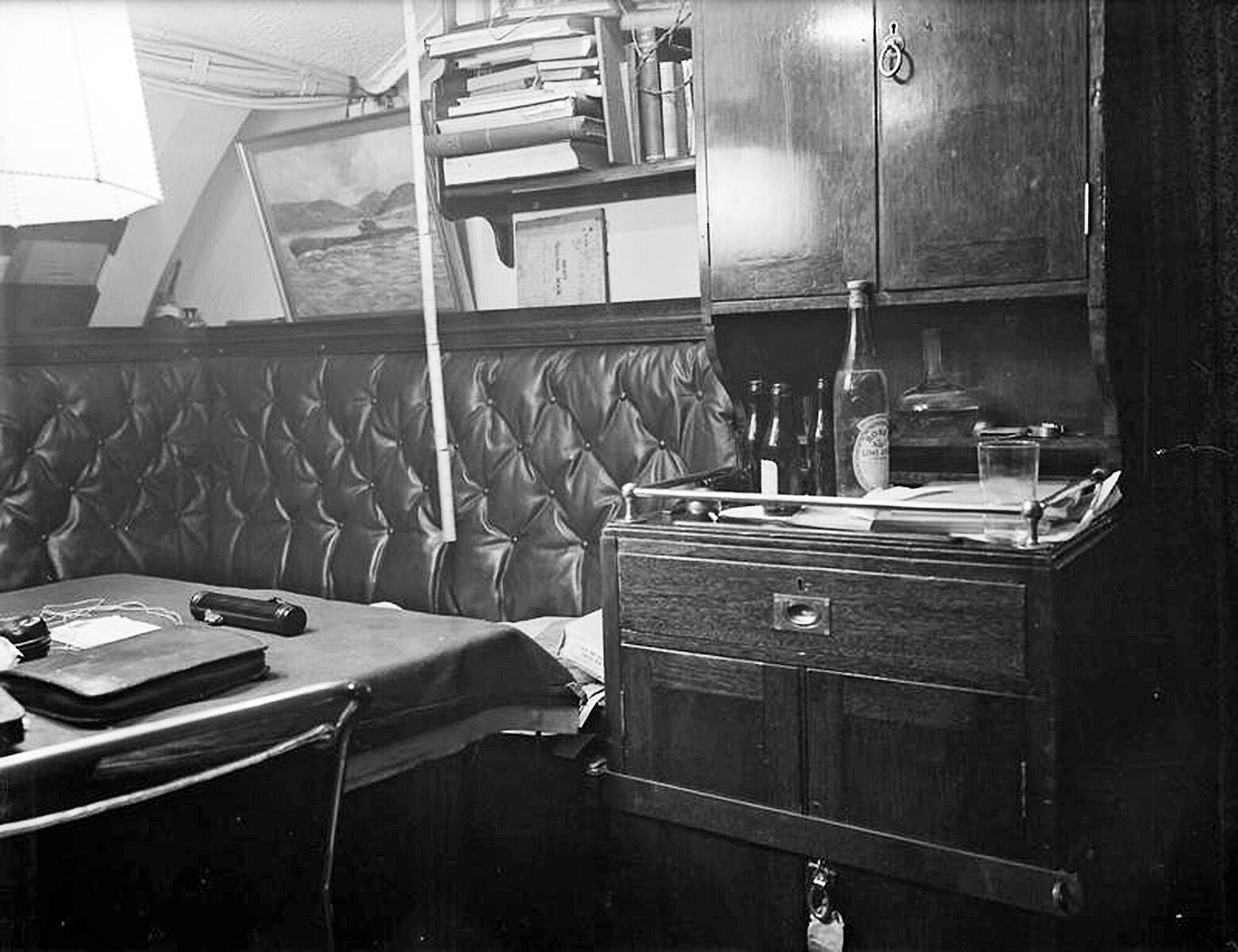

The forward end of the wardroom. The drinks cabinet - vital stowage - is on the right, with a bottle of Rose's Lime Juice and what look like beer bottles. While there was no formal restriction on drinking at sea submarine officers generally limited themselves to a glass of sherry with supper. A sherry decanter sits in the fiddle at the back. The crew had a beer ration, and also a daily rum ration. More reference books are crammed into the rack, next to a painting of Tribune on the bulkhead.

Not everyone slept in their messes. Triumph had a number of bunks in the starboard forward passageway. Note how little headroom the top bunks have. But at least, witht the curtains closed, would give a little privacy.

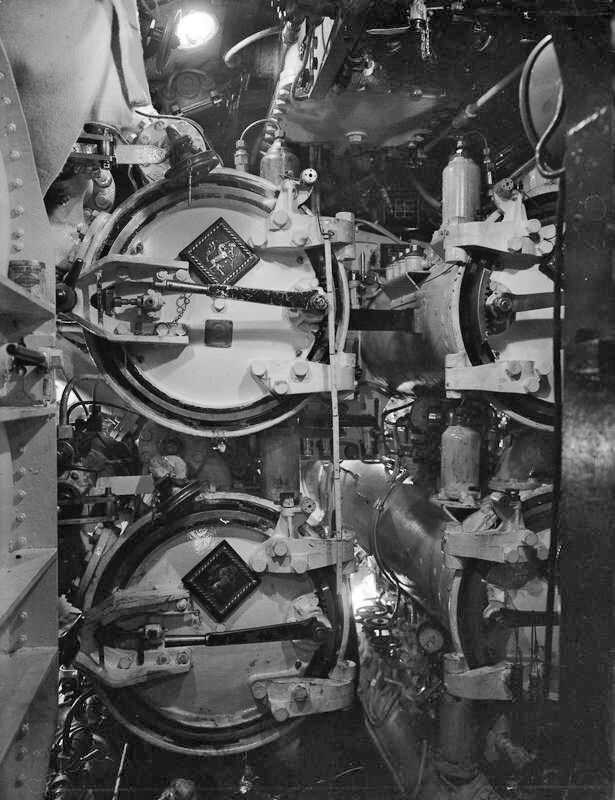

A submarine's principal weapon system was her torpedoes. Most of these were stored in the Torpedo Stowage Compartment, shown here. (In the Ts four torpedoes were stowed in tubes outside the pressure hull as well). The torpedoes, 23 inches in diameter and weighing about as much as a car, are stowed in racks port and starboard. We can see the inner doors of the tubes through the oval door forrard. To reload a tube the racks were built out into the centre of the compartment and the reload was rolled in its cradle to be in line with the tube, then hauled into the tube using a bock and tackle.

There are two more racks below the deck, and the square deck panels can be lifted to gain access. The TSC was the largest compartment in the boat, and was also a storage compartment for food, and a sleeping compartment too for junior rates. We can see hammocks rolled up on the deck, and spare clothing hanging here and there.

In the roof of the compartment (the deckhead) are two curved rails. These drop down and are connected to other rails which pass up through a large hatch for loading and offloading torpedoes. When not in use the rails also become storage, in this case for a generous supply of Corn Flakes.

Here is a torpedo being loaded. It is rolling down the loading rails, for stowage in the rack on our left. This photo gives a better perspective on how small even this large compartment was.

The torpedo is now fully in the compartment, and its weight is held by tackles slung from the deckhead. Below it, its rack lies ready to receive it, having been rolled to the centreline.

The gunnery officer, also responsible for torpedoes, checks the weapon before it is lowered. Note the cigarette - torpedoes were famously stable weapons!

The torpedo will eventually end up here, in its tube. We can see four tubes here. Two more are below deck level. On the left of the doors we can see the Thetis Clip - a wing-shaped clip added after Thetis sank by accident in Liverpool Bay. This prevents the door from accidentally opening inboard if the tube is open to the sea.

And the starboard tube door.

Staying with the subject of torpedoes, Triumph had two external tubes athwart the bridge. This photograph shows one of these being reloaded. We can see the torpedo on the left of the open deck plating, which has been folded back to give access. In the later Ts (like Tribune) these external tubes were reversed to give two stern-firing tubes. Tribune's faced forwards and it is not clear why here the torpedo's warhead seems to be aft.

The galley cooked food for everyone. In Triumph the day was reversed, with breakfast after sunset and supper after diving at dawn. This space had to produce three meals a day for 62 men. The cookers and ovens were, of course, electric.

A galley is no use without a chef, one of the most important men aboard, since morale falls apart pretty quickly if a boat's food is not up to snuff.

However, a good chef doesnt have to be a cheerful chef.

Aft of the messes (and the CO's cabin, which was not in the photographs) is the control room - the operations heart of the boat.

Looking aft, we can see the voice pipe from the bridge, used when the boat is surfaced, and just below it is the helm. On the right of the picture are the two planes controls - fore and aft, each with a rather uncomfortable seat for the planesman. The nearer tube is the search periscope, with its optics below the deck plating in the down position. The ladder leads up to the bridge, then the smaller attack periscope is aft of that. Two men are standing in the passage to the rear half of the boat.

.jpg)

This is the starboard side of the control room seen from the same vantage point. In the near foreground is the chart table, and above that is the Torpedo Data Computer (or fruit machine) an electromechanical computer used to calculate the "angle off" for torpedo aiming. It is discretely covered with a wooden blank as it was a secret piece of kit. Aft of the TDC is the blowing panel, for controlling ballast tank flooding and blowing (with a chief's cap hooked on a valve). Aft again is the mine detecting sonar screen.

The control room from aft looking forward. Both periscopes are now up. We can see the helm, and above it the oblong compass tape that shows the boat's heading.

This is the mine-detecting sonar. The soulful looking man has probably been posed to give the set designers some idea of scale.

The ladder in the centre of the control room leads to the conning tower hatch (or "the lid"). A separate ladder and hatch (forward) led to the gun platform.

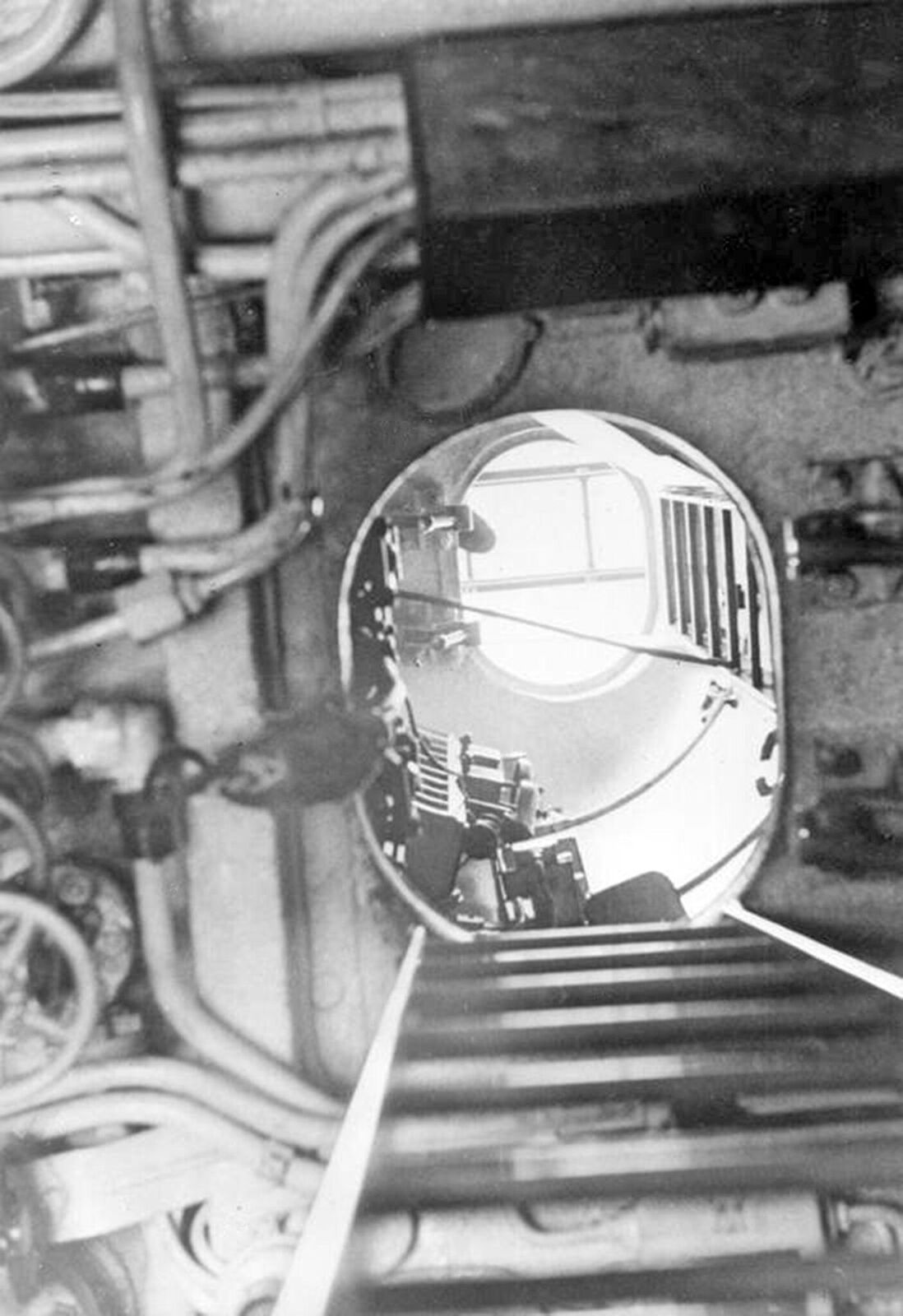

This is the upper hatch seen from above. The drain holes are designed to empty the bridge of water quickly as the boat surfaces.

The next space aft of the control room was the wireless office. This is surprisingly spacious. Boats rarely transmitted at sea, but often received new patrol orders and sitreps while on patrol.

While under way on the surface signals were passed to ships in visual range with a small hand-held searchlight called a signal lamp. The lamp has a venetian blind operated by a trigger, and a good operator can send and read 20 words per minute. Signal lamps were also used to verify the identity of unknown ships. If you got your reply to a challenge wrong you could be (and sometimes were) sunk by your own side.

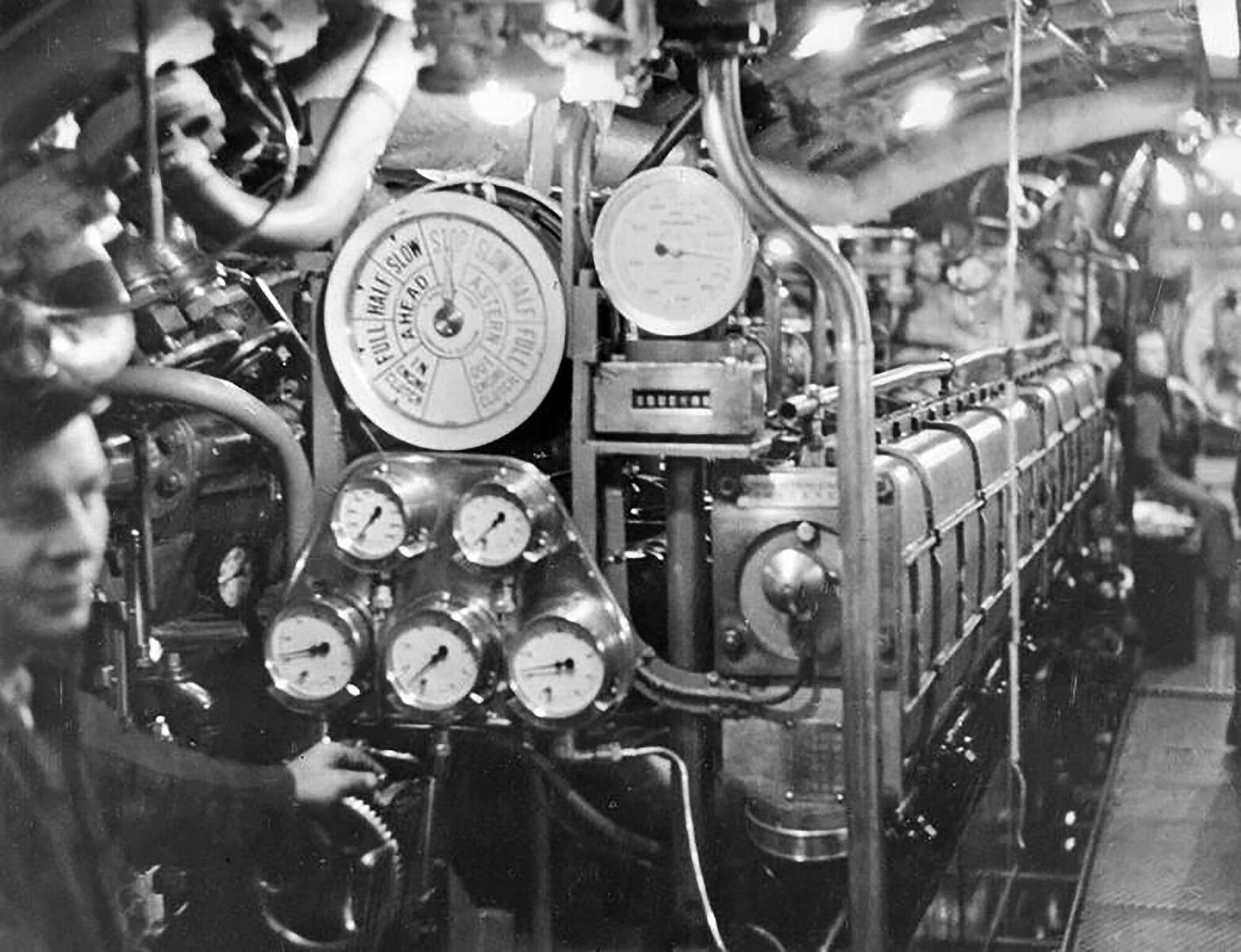

Triumph was powered by two diesel engines, which could be clutched to large electric motor/generators. This is her starboard engine. There was no sound insulation.

There was very little space in which to work on the engines, but the tiffs could remove and replace pistons, cylinder liners, valves, and even crankshafts.

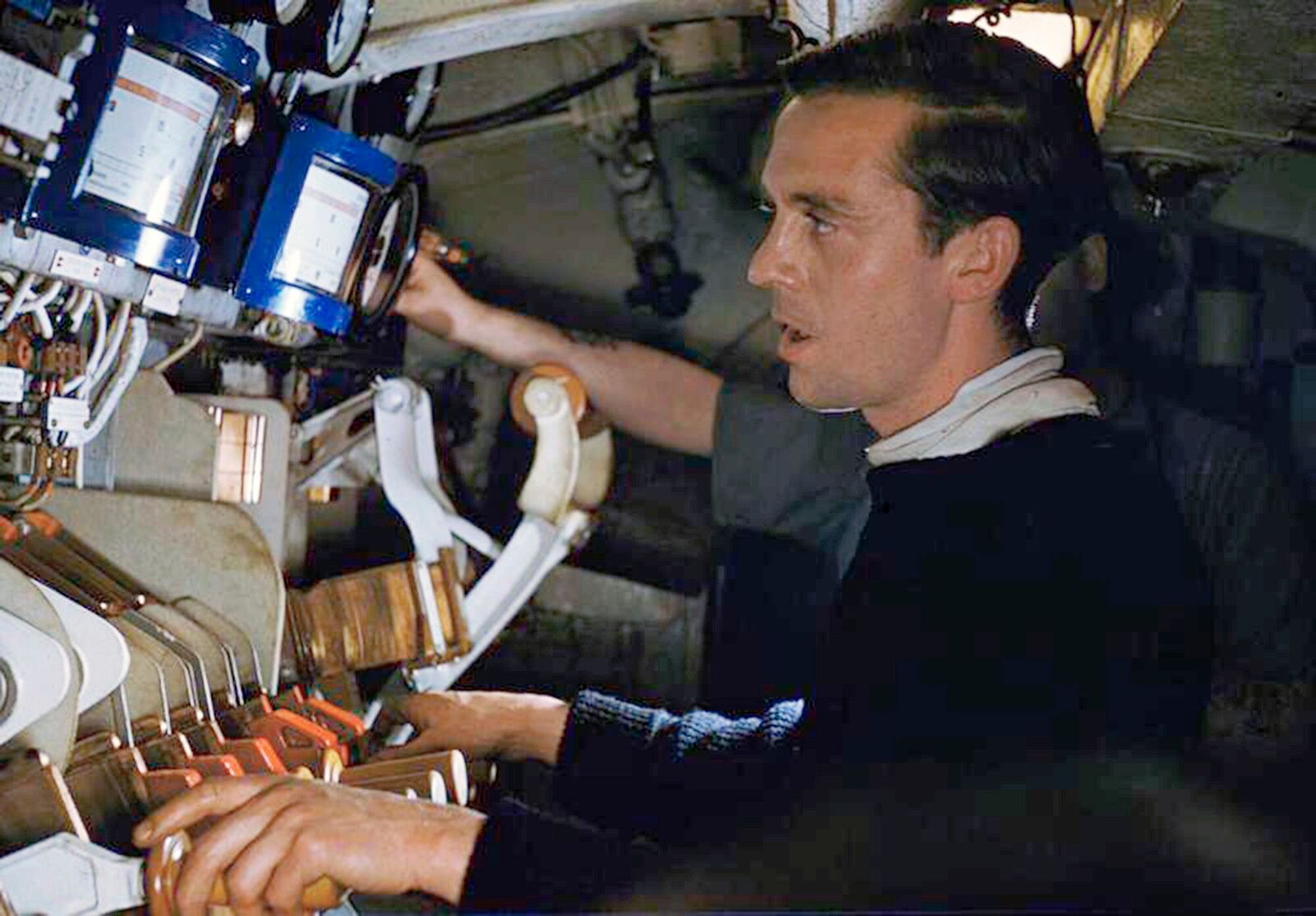

This colour photo gives a much more real feel for the lack of space.

The warrant engineer (the Chief) is about to start one of the main engines. Starting was effected with a large shotgun-type cartridge.

Aft of the engine room was the Switchboard. Electric motors (which also acted as generators) were below the deck plates. Here we can see the bus bars and breakers which controlled the flow of current from the batteries to the motors.

The Marine Engineering Officer (the MEO) stands at the breakers reading current flows off the meters.

A stoker mans the breakers. Under electric power speed was adjusted by running batteries in series or in parallel (grouping up and grouplng down). The dial in front of the stoker is the revolutions counter for the port propellor.

Aft of the Motor Room is a lobby, with the escape tower. We can see the forward hatch open, while the after hatch (to the stokers' mess) is shut. The tower leads to a deck hatch, and was intended to allow escapes from depth. In fact we cant think of an occasion when men in a sunken boat had an opportunity to use the escape tower successfully. Escape hatches were often bolted or welded shut, as experience showed that they could be burst open by depth charges. Sometimes depth charges so compressed the hatch that the rubber seal was squeezed out and hatches would leak.

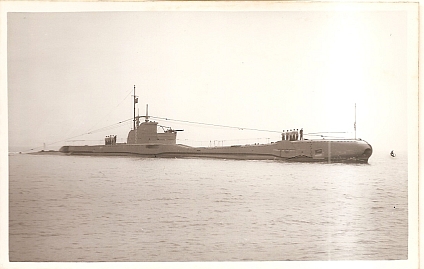

Triumph from outside. The men on the casing are clustered around the torpedo loading hatch. We can see the gun turret with its 4 inch gun (the whole turret rotated). Aft of that is the bridge. The big tubes protect the periscopes. The bridge has a helm, but the boat was usually steered from below in order to reduce the number of men on the bridge.

Triumph did not carry radar, so survival depended on seeing the enemy before being seen. A boat on the surface at night would have four lookouts. A boat that failed to detect an approaching enemy would not survive. The device in front of the lookout is the surface torpedo aiming sight.

Tribune (wearing her film name of Tyrant) setting off on patrol. The officers are in number 5s (no working dress here). We can see that the bridge was actually quite spacious.

Triumph's forecasing. We can see the torpedo hatch inside the square opening. Her planes are folded out for diving. There is quite a lot of working space. On the night Triumph landed supplies on Antiparos some five tonnes of fuel and food had to be manhandled out of the hatch and onto this casing, for passing into folboats and fishing boats, all in the dark.

This still from Close Quarters five some idea of how hard that must have been.

Heading out on patrol. The fore planes are folded in order to reduce pounding (and damage).

Good hunting, and safe return.

At the start of WW2, 2,641 men were serving at sea in operational boats in the Royal Navy. By the war's end, 2,100 were dead. At 80% the submarine service experienced the highest mortality rate of any UK service (including Bomber Command).

There are several submarine memorials in the UK. At Alrewas, the National Memorial Arboretum, the memorial is simply this...

If you believe that this is not a fitting tribute, please contact us using the contact page on this website.

August 2017 - Another relative joins the Triumph family - Angela Pugh, cousin to Jack Underwood.

March 2017 - recording of Triumph's 1st Lt. I came across this recording of Richard Gatehouse, who was 1st Lt of Triumph from November 1940 to June 1941, leaving her in Gibraltar. It is from the IWM collection. http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011948.

Feb 2017 - Another relative joins the Triumph family. Welcome to Cathy Ferguson, who is related to AB George Newby. Cathy found George via the pyramids photograph.

Cdr John McGregor, who served as MEO in a T-boat in the 60s, has let us have this note on who did what...

What did Triumph’s crew do on board?

I served for two years in HMS Truncheon a sister submarine to HMS Triumph. Following the Triumph meeting at Alrewas on January 9th when I met so many of the relatives and descendents I promised to explain the crew organisation and what they did on board.

Every submariner had to pass a verbal and practical exam known as the BSQ (basic submarine qualification) which tested his knowledge both of the submarine and of emergency procedures. If he didn’t pass he would lose his submarine pay and nowadays he (or she) wouldn’t be entitled to wear the submarine badge. There is no room for passengers in a submarine and every man played an essential part.

Triumph’s ships company as shown in the crew list totalled 60 men:

Captain and 5 officers

Seaman Department 2 Chief Petty Officers, 3 Petty Officers, 5 Leading Seamen, 12 Able Seamen, 1 Petty Officer Torpedo Gunners Mate,

Engineering Department 1 Chief Engine Room Artificer, 5 Engine Room Artificers, 1 Electrical Artificer, 1 CPO Stoker 1 Petty Officer Stoker, 3 Leading Stokers, 11 Stokers

Communications 1 PettyOfficer Telegraphist, 1 Leading Telegraphist, 3 Telegraphists, 1 Leading Signalman

General 1 Petty Officer Cook, 1 Leading Steward

The Captain was always on call. His cabin was at the forward end of the Control Room in a good position to overhear what was going on. A shout of ‘Captain in the Control Room’ or ‘Captain on the Bridge’ would summon him for any emergency or unusual event. It was traditional for him to have his breakfast in his cabin but he would have lunch and dinner in the Wardroom.

A T-Class submarines carried 4 or 5 officers with the 1st Lieutenant as the second in command. The Navigating officer and Torpedo Officer were known as the 3rd and 4th hands and the Engineer officer was responsible for all engineering and electrical aspects. The 5th hand was often under training and his job was as Correspondence officer, having to type up all reports and letters. There were four bunks in the Wardroom which had to be stowed for all meals and three outside in the passageway. All officers were expected to keep watches both on the bridge and in the Control Room when dived.

The next Mess forward of the Wardroom was the ERA’s Mess presided over by the Chief Engineroom Artificer. All ERA’s underwent a long apprenticeship and became skilled technicians rewarded by early promotion to Petty Officer and Chief Petty Officer. Three of the ERA’s kept watch in the Engine Room particularly when the diesels were running and two others were the ‘Donk Shop Horse’ who worked on all engine room defects and the ‘Outside wrecker’ who repaired all defects in the rest of the submarine particularly on the water, air and hydraulic systems. The Outside wrecker’s action station was on the pumping and blowing panel in the Control Room and he also raised and lowered the periscopes and masts. The final Artificer was the Electrical Artificer who became essential during WW2 as the electrical systems became more complex.

The next Mess forward was the Seamen Senior Ratings Mess presided over by the Coxswain, the senior rating on board. His duties included discipline, administration and if anyone was injured he applied medical care from a book. The other CPO was almost certainly the Torpedo Instructor (or TI) in charge of moving and firing the torpedoes assisted by the PO Torpedo Gunners Mate. In the Mess were the other Chief & Petty Officers – the Chief Stoker, the Sonar PO, the Radio PO, the PO Cook, and the PO Electrician. Each would be responsible for several ratings in their sections except for the Cook who was on his own in the tiny galley with maybe just one seaman to assist.

The Junior Rates Mess was presided over by a Leading Seaman. There were as many as a dozen bunks for most of the Seamen as well as the Leading Steward, and the electrical and radio specialists. Those without a bunk had to sleep in the Torpedo stowage compartment on the stowage racks amongst the torpedoes.

I was asked what the Able Seamen did. Four ASDIC (nowadays Sonar) ratings would take it in turns to be on watch in the sound room and the Telegraphists and Signalman would handle the signals. When moving or firing torpedoes about six seamen would work under the CPO TI. When entering or leaving harbour, seamen would work on the submarine casing handling the steel wire ropes for securing the submarine. When firing the gun the PO Gunlayer would be assisted by two Seamen whose duty was to load and fire the gun in less than a minute after the submarine surfaced [Robert Don records in his letters home that the Triumph standard was six aimed shots within one minute of the hatch being opened]. When landing agents or rescuing escaped POW’s (a task given frequently to Triumph) Seamen would launch and crew the ‘FOLBOATs’ (collapsible canoes) and paddle them ashore.

The final Mess was the Stoker’s Mess at the after end of the submarine. On watch in the engine room were a Leading Stoker and a Stoker with another Stoker right aft known as the after ends watchkeeper. In the Motor Room were two electrical mechanics who operated the main motors and large electrical distribution switches. A Leading Stoker and a Stoker assisted the ‘Outside Wrecker’. As in all the watchkeeping positions the normal organisation was to have three watches so three men covered each position.

January 2017

Families gathered for the 75th Memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum

32 members of the Triumph family gathered at Alrewas on Monday 9th January to commemorate Triumph on the 75th anniversary of her loss.

While the weather did its best to discourage, we held a service of remembrance at the Submariners Memorial, led by the Rev Tim Flowers of the Mercian Regiment. Tim lives nearby, and often officiates at Alrewas, and he made this one very personal and moving. During the service we laid a wreath to our crew.

After the service everyone gratefully returned to the cafe at Alrewas - largely deserted on this cold January Monday. Few families had met before so many new friends were made. Adam Theobald brought a complete file of papers, photographs and citations, while John Underwood brought his uncle's last letter home, and a photograph of his grandparents at Buckingham Palance.

We were very happy to have a guest as well - Commander John McGregor RN OBE, who was a senior submarine nuclear engineer, and who also founded the Neptune Association, to commemorate the crew of HMS Neptune, lost off Libya with (nearly) all hands only a month before Triumph.

John McGregor chatting with Tim Flowers after the service.

At the end of lunch we gathered for a group photograph.

Thanks to everyone for coming. Here's to the next one, perhaps in Greece.